This Black History Month, the Walsh School of Foreign Service (SFS) is telling the stories of Black trailblazers in our community and their accomplishments in face of adversity, including at SFS and Georgetown. Learn more about Black History Month celebrations and honors at Georgetown at the university’s dedicated webpage

Professor Gwendolyn Mikell’s quotations in this story come from her Life of Learning Address, which she delivered at Georgetown’s Spring 2017 Faculty Convocation.

When Professor Gwendolyn Mikell first decided to come to Georgetown, friends and coworkers advised her to reconsider. In 1976, Georgetown had never tenured a Black person, nor were there any tenure-track Black faculty. “Well,” she replied, “I guess I’ll have to be the first.”

The first tenured Black woman at Georgetown, Mikell spent 47 years with the university, recently retiring in August 2021. Mikell led a remarkable career, chairing the Department of Sociology and Anthropology from 1992-2007 and directing the African Studies Program from 1996-2007. Off campus, she is a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations and also held positions such as President of the African Studies Association and Jennings-Randolph Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

Coming of Age in the Civil Rights Era

Mikell’s passion for studying race and justice stems from her Chicago upbringing and summers spent with cousins at their grandparents’ Mississippi farms. During the journey from city to countryside, she recalls how white drivers would try to rear-end the family’s car. To a young Mikell, successfully navigating the perilous roads and emerging out of Southern Illinois felt like victory.

As she attended high school on Chicago’s Southside, “race was an ever-present influence in the background.” Schools were still segregated, and the civil rights movement slowly engulfed the nation. With the support of determined Black teachers who recognized Mikell’s intellect, Mikell pursued her interests in biology and attended science fairs. In the fall of 1965, just as the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 took effect, Mikell entered the University of Chicago’s freshman class as one of 17 Black students.

Continuing with her studies, Mikell explored the social sciences as a source of activism. As desegregation battles and the Black Power movement began to gain traction in the United States, Mikell connected with fellow Black peers and academics. “We understood in a fundamental way that it ‘had taken a village to raise a child’ and that with these gifts came an obligation to work for racial justice, and opportunity for others,” she remembers.

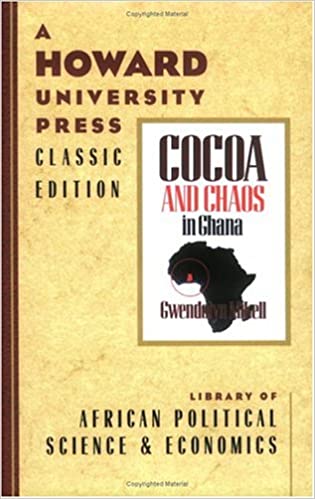

After receiving a grant to pursue research in the country, Mikell traveled to Ghana where she studied linkages between culture, economic and politics in cocoa cash cropping village communities, eventually culminating in her book Cocoa and Chaos in Ghana. While completing her PhD dissertation at Columbia, she sought further interdisciplinary exchange between intellectual and diplomatic communities, eventually bringing her to Georgetown.

Being “the First”

Mikell is admired today as a trailblazer for Black faculty and students of the university. However, her accomplishments did not come without challenge. Over her many years at Georgetown, she consistently battled resistance to racial justice within the academy.

“I have so many anecdotes about the initial refusal to recognize a Black woman as a real professor,” Mikell remarks. “The students who would not come into my office, and the campus officials who refused to believe that my faculty ID card was real, and the colleagues who would not take my scholarly discipline or my research on the Black world as legitimate.”

During her time on campus, Georgetown’s faculty severely lacked diversity. Over the years, Mikell witnessed many Black faculty members arrive on campus only to leave months later. Some cited unhappiness at inadequate mentorship, while others pursued institutions which appeared to value their expertise more than Georgetown. “Few other Black faculty members were asked to chair their departments, assume a named chair, become Dean or to be recognized in a special way by the university,” stresses Mikell.

Despite facing numerous structural barriers to success, Mikell credits Black colleagues across Washington, DC, for keeping her “intellectual fires” alive. Relationships with Black academics across the city provided a space for Mikell to develop her ideas and even gain introductions to people who had known critical figures like Alaine Locke and Zora Neale Hurston. Mikell stresses, “Moving through promotion and tenure taught me about the social reinforcements that Black faculty members need in order to survive.”

Building a More Equitable Future

On campus, Mikell was a key supporter of recruiting faculty of color and creating more opportunities for the study of Africa at Georgetown.

Beginning in the early 1980s, student demands for the university to implement sanctions in protest of apartheid in South Africa and to offer additional courses on Africa led to the founding of the African Studies Program at SFS. Mikell brought together a broad cohort of her colleagues, focusing on issues of globalization and institutional diversity and leading the way to expand the school’s course offerings in other areas, too.

“We expanded the SFS curricula to include the Culture and Politics and then the Science, Technology and International Affairs major,” she recalls. “I thought to myself that Georgetown was catching up, and that perhaps we would make our mark in academia and on the world.”

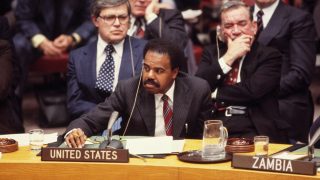

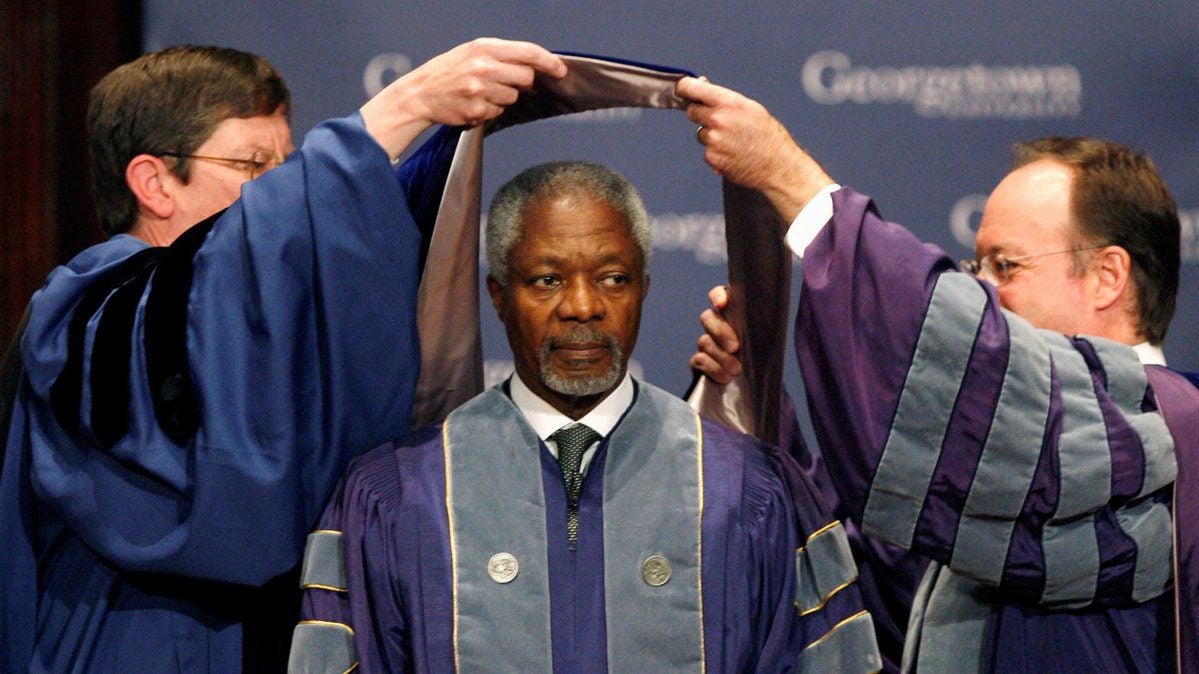

In 1995, Mikell attended the landmark Beijing World Conference on Women, during which former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously declared “women’s rights are human rights.” After a fellowship with USIP, where she expanded her scholarship to study women’s peacebuilding in Africa, professionals at the United Nations and Carnegie Foundation asked Mikell for critical analysis of UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s two tenures. Turning to Georgetown for assistance in her examination, Mikell found the support of University President John J. DeGioia, who agreed to a conference which featured Annan as a guest speaker and conferred him an honorary degree.

A Lasting Legacy

Reflecting on the future of Black faculty and students at Georgetown, Mikell recognizes the tension between acknowledging progress and challenging the university to do better.

In the current moment, “American institutions are challenged to rise to the occasion,” says Mikell. The creation of groups like the Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation initiative, Working Group on Racial Justice and African-American Studies Department at Georgetown represent real change. However, “My colleagues at other educational institutions are watching us,” Mikell cautions. “They believe we can set a new university paradigm for merging research and praxis on U.S. racial justice and public policy challenges.”

Mikell’s persistent advocacy for racial justice continues to shape the university today, and her mentorship has inspired generations of students. Among them, U.S. Representative Stacey Plaskett (SFS’88, D-VI) remembers Mikell as the first Black teacher she ever had. “I can recall the emotions that came over me,” says Plaskett. “I had not had that kind of model in my life before, and how important seeing her in command of her subject matter was to me as a young woman.”

“When I encounter SFS grads, spanning from the 1980s to the 2020s, they still talk about Gwen’s classes and the influence she had on their lives,” says Scott Taylor, SFS vice dean for diversity, equity and inclusion and a former director of the African Studies Program. “Gwen Mikell’s legacy of leadership, mentorship and scholarship is indeed a durable one. I, and many others, have been fortunate to stand on the shoulders of a pioneer.”