The first female students arrived at the School of Foreign Service in 1943 and—although they would face a variety of unique obstacles, limitations, and quota systems that lasted nearly three decades—women have been at SFS ever since.

Women, whose admission to SFS started as a wartime necessity to fill large drops in male enrollment during World War II, would have progressively more opportunities over the 1940s, 50s and 60s. The SFS women of this era broke new ground while the school provided them with opportunities to access courses in higher education that had previously only been available to men.

“Camp Georgetown” Admitted Women to Fill Empty Seats

Admission of women to the School of Foreign Service began as a financial necessity in 1943 when the draft for World War II led to big drops in enrollment of male students. In his 2010 history of Georgetown University, Robert E. Curran describes how in 1942 Jesuit administrators held a special meeting to prepare for keeping Georgetown afloat during the war. The military draft was, by this point, set to deploy most of Georgetown’s usual college-aged male students to the war. “They had no idea how many students would be there for the next year. One pool of potential applicants that the draft would not touch, of course, was women,” Curran notes. Admitting women to Georgetown’s graduate school was one solution to this problem. Beyond their nursing schools, Jesuit universities like Georgetown had not traditionally admitted any women. It would still be decades before Georgetown College would allow women to enroll.

Jessie Pearl Rice, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), was among the first women to take classes at SFS. Rice, the assistant director of the WAC, was “one of 43 women admitted for the first time to the School of Foreign Service,” according to a 1943 newspaper article. She was “outranked by only two or three full colonels,” among the population of male army officers at Georgetown at the time. In fact, most of the university’s population in 1943-1944 came from one of several wartime military programs housed at the school. If you had arrived at the Healy Gates of “Camp Georgetown” during this time, you would have been greeted by a sentinel and block-letter signs with the words “Military Reservation—Restricted” inscribed on them.

Rice and her fellow female students mostly took language classes in the evening and worked during the day, but Rice also took a geopolitics class with Father Edmund A. Walsh, S.J. According to an article in The Washington Post: “Wartime demands are responsible [for the school admitting women]. The break in masculine tradition is being made to help women speak more widely in seven languages.” Women could enter nominally as “language students,” but could also apply credits towards a degree in Foreign Service, which several did.

The announcement that the School of Foreign Service was set to admit women, however, was not without a stern warning to prospective female students. These women could only enter classes, school officials warned, if they “have the serious intention to pursue this type of instruction and do the assignments, possess an aptitude for one or more foreign languages or seek a knowledge of the language of their choice for some present or future employment or for some definite service or for practical contact with foreign affairs.”

Post War Language Needs Bring More Women to the SFS

When men began returning from the Second World War and SFS experienced a surge in G.I. enrollments starting in late 1944, women continued to take courses, especially in foreign languages. What had started as a means to fill empty seats left by men sent to war soon became an opportunity for the school to fill a pressing government need to have civilian employees with better language skills. Mary Alice Sheridan and Anne S. Lawrence were among the very first women to graduate with BSFS degrees from the School of Foreign Service. They accomplished this thanks in part to credits transferred to SFS from the other colleges they had previously attended.

Father Edmund A. Walsh, then Regent of the school, told The Washington Post in 1944, “The most striking adaptation and development in the School of Foreign Service will be in the teaching of foreign languages, and the United States will be deeply interested after the war.” These language courses, Walsh added, were open to women. The number of women enrolled in SFS, all of whom took night classes, would fall to 22 by November 1947. But by this point, several more women had already graduated with BSFS degrees. Admission of women would continue rise, especially in 1949 with the opening of the Institute of Language and Linguistics (ILL).

Gerard Yates, dean of the Graduate School, complained to President Guthrie in 1948 that “women students are coming to be a part of the undergraduate study body,” according to Curran’s account. “While they are few in number,” Yates wrote to Guthrie, “their presence is anomalous and indeed unwelcome.” Despite this resistance, Curran notes, “the School of Foreign Service continued to maintain a coed presence of approximately fifty [women students].”

By the summer of 1949, Father Walsh had acquired for Georgetown the property of the former Academy of the Sacred Heart on Massachusetts Avenue, which would become home to the Institute of Language and Linguistics (ILL). In its second year, 1950-1951, ILL’s enrollment had reached nearly 250 students, 40% of whom were women.

SFS Integrates Women and Men on the Hilltop for the First Time in 1954

Women continued to enroll both in the Institute of Language and Linguistics and the evening division of SFS through the early 1950s. When Sherman L. Cohn, today a Georgetown Law professor, was an undergraduate at SFS, he served as editor-in-chief of the Foreign Service Newsletter in 1952-1953. There were several women on the staff of the Newsletter that year including Eileen T. Burns, Mary Grassley, and Patricia Miller.

It was in 1954 that Father Frank Fadner, S.J., Regent of the School of Foreign Service, first allowed a small number of women to take classes on Georgetown’s main campus during the day and with the male students. This was done in part because Fadner feared an impending merger of the School of Foreign Service with Georgetown College. Fadner saw this as a way of further distinguishing SFS from the College and precluding such a merger.

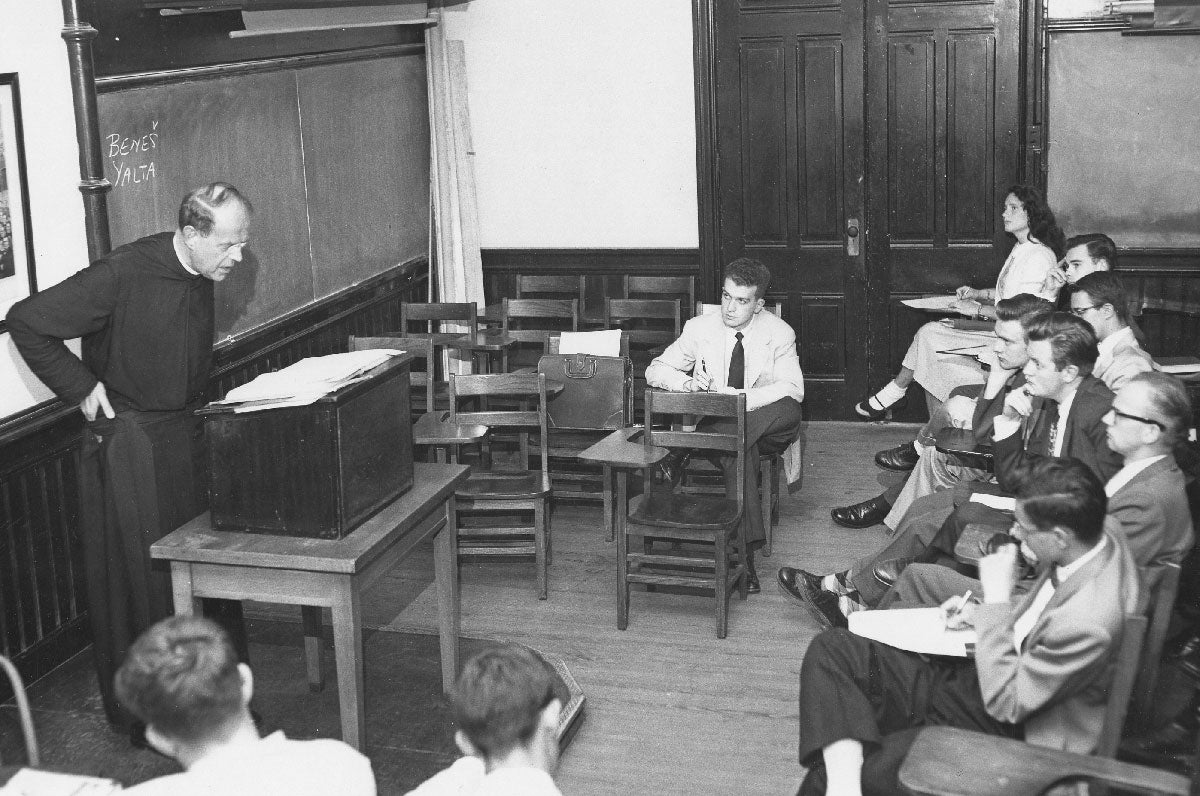

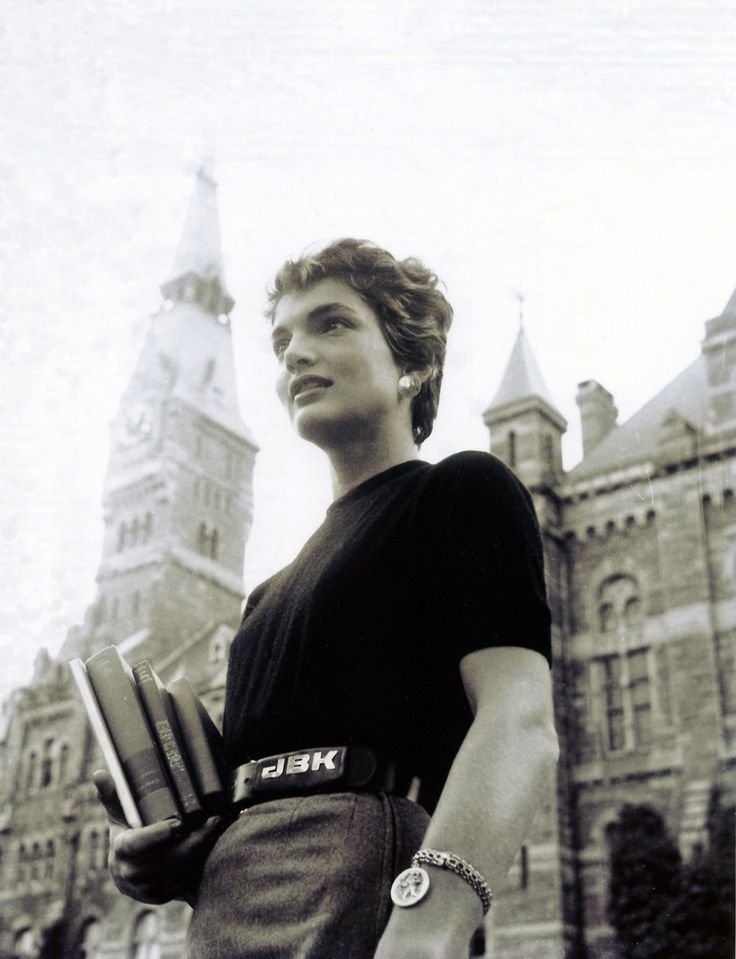

In the spring of 1954, six women were admitted to take regular SFS classes in a pilot project. This group of six included Jackie Kennedy, wife of then Senator Jack Kennedy, as well as socialites Daviette Hill, Frankie Smith, and Stuart Smith. In Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis: A Life, biographer Donald Spoto notes that Jackie Kennedy took a course in political history at SFS, just four blocks away from the Kennedys’ Georgetown home. Although she already had a bachelor’s degree from George Washington University, Mrs. Kennedy wanted to “enrich herself and learn about one of her husband’s two consuming interests.” Except for the nursing school, Spoto writes, “[SFS] was, at that time, the only school at the university that admitted women.”

A feature article ran in McCall’s Magazine that year, “The Senator’s Wife Goes Back to School,” featuring photos of Jackie Kennedy around campus and in her political history class with Jules Davids, a professor of diplomatic history at SFS. “It fascinates Jack to compare Jackie’s classroom theories with his own practical experiences,” the McCall’s article put it. “Evenings she helps him with his major speeches.” Soon after, JFK would seek help from the same Professor Davids to write his 1957 book Profiles in Courage.

Ambassador Melissa Foelsch Wells, one of the first women on the Hilltop, recalled in her diplomatic oral history interview how in her first year at SFS, she could not go on campus in the daytime because they didn’t let women in. By the fall of 1954, however, twenty-five women were part of the regular SFS class on the Hilltop. “At Georgetown, when I was a student there, I had a lot of good friends, male friends, not one of them romantically involved. There was a little pack of four or five of us; I was the only woman,” Wells said in her 1984 interview. “We were cramming for the history of foreign relations, and we’d spend the whole night together, sort of, asking each other questions, going to sleep on the floor, whatever it was. It was absolutely natural. There was never any funny business, nothing.”

Quota on Women’s Admission Finally Lifted in 1970

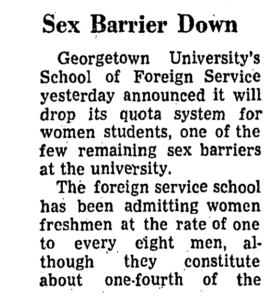

While women continued to gain more representation on campus, in government, and the wider foreign service community in the 1950s and 60s, it was not until 1970 that the quota limiting female admissions to the School of Foreign Service was finally lifted. These efforts were brought about in large part thanks to the Foreign Service Women’s Association (FSWA), founded during the 1950s by some of the first women on the Hilltop. FSWA paired incoming students with “older sister” mentors and also held speaker events, playing a prominent role in the social scene on campus.

An article on the subject in The Washington Post on February 18, 1970 proclaimed “Sex Barrier Down.” Women, the Post article stated, had come to constitute one-forth of the school’s 959 students despite the nominal quota that had, until then, “been admitting women freshmen at the rate of one to every eight men.” The same article noted that Georgetown College of Arts and Sciences “admitted women for the first time this year, but is maintaining a quota of 50 women freshmen. A male sex barrier will fall next September when the school of nursing drops its ban on male students.”

Women had now become an integral part of the life of the School of Foreign Service, a process decades in the making. Many of these pioneering first women of SFS would go on to use their foreign service education to make their own impact across fields, especially in diplomacy, where their work and legacy continues to live on.