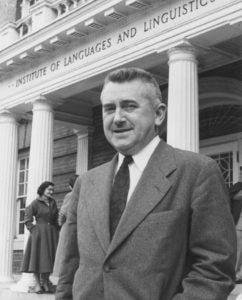

Leon Dostert, one of Georgetown’s most influential alumni, not only left his legacy on the University with the creation of the Institute of Languages and Linguistics, but also left his mark on the world in the field of translation and interpretation, most notably at the Nuremberg Trials.

Dostert was born in France, and orphaned at a young age. He grew up during World War I, in a town on France’s border with Belgium during the German occupation. He picked up German and English, and perfected his native French. His trilingual capabilities would lay the foundation for his pioneering work in translation. He worked for both the American and German armies during that time doing translation.

In 1921, American troops sponsored Dostert to come to the United States. He went to high school in California, where it is rumored he was exempt from English classes that native speakers were required to take because his grammar and understanding of the language were already strong. He then began undergraduate work at Occidental College in 1925 before arriving at Georgetown.

Dostert graduated from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in 1928, and continued his education with a Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from the College in 1930 and a Master’s degree in 1931. While studying at Georgetown, he also taught French at the University. In total, Dostert spoke French, German, English and Russian.

He served as Chair of the Languages Department at Georgetown in the 1930s and continued to teach French and French Civilization courses. Through his connections in D.C., he befriended Thomas Watson, Sr., Chairman and CEO of IBM, a relationship that was fruitful for both men for over two decades.

When World War II began, Dostert served in the French Army in their Washington embassy for two years, and then became an American citizen and immediately enlisted in the U.S. Army. He worked in intelligence, in the precursor to the CIA, and was deployed to North Africa, where he was General Eisenhower’s personal translator and also did translations for French war hero General Charles de Gaulle. By the war’s end, he was a colonel and had received military honors from the United States, France, Tunisia and Morocco.

Dostert had become well known in the field of translation after the war, and was asked to head up the interpreting systems for the Nuremberg Trials in 1945. He created the new subfield of simultaneous translation, where a translator hears information in one language from a source, often an earbud, and then translates in their head and speaks the translation into a microphone or recording that another party can hear. He used equipment designed by IBM, provided for him by his old friend, Thomas Watson, Sr., IBM’s CEO.

At the trials, Dostert was Chief Interpreter, and led three teams of 12 translators, so the trial could be broadcast in English, German, Russian and French simultaneously. Anyone in the courtroom could pick a target language and have it delivered to them through a headset. The countries participating in the trails were pleased with the efficiency and accuracy of the translation, as well as the outcome of the trials.

During the Nuremberg Trials, Dostert was asked to lead the translation for the newly-created United Nations. The U.N. preferred consecutive translation, which is choppier and requires significantly more back-and-forth messaging, but Dostert and Watson at IBM convinced the United Nations to use the IBM equipment for simultaneous. Today, simultaneous translation is used at the United Nations for 6 different languages – English, Chinese, Spanish, French, Russian and Arabic.

After his work at Nuremberg and the U.N., Dostert returned to Georgetown and collaborated with Father Walsh, Dean of the School of Foreign Service, to open a new program: The Institute of Language and Linguistics. A large room was built inside Poulton Hall, filled with tape recorders and sound-proof booths, where students could work on their language skills by listening to auditory drills without interruption. IBM provided the same materials they had at the U.N. and Nuremberg to Georgetown to begin this project, which helped expand the study of languages at the University dramatically.

In 1954, Dostert first witnessed machine translation, where a computer inputted sentences from a Russian organic chemistry textbook and outputted an English translation. He proceeded to found the Machine Translation Research Project at Georgetown in 1955, using funding from the National Science Foundation and the CIA, to continue the technology’s development.

Dostert served as Dean of the Institute of Language and Linguistics until he was succeeded by Professor Robert Lado in 1960. He received multiple awards from the University and was elected Vice-President of the National Federation of Modern Languages Teacher Association in 1959, and became President in 1960.

Dostert left Georgetown University in 1963 because of the stigma he experienced after getting divorced, and he returned to Occidental College in California. At Occidental, he transformed the school’s language and study abroad programs. He taught classes until he retired at 65, and passed away only two years later on September 1, 1971. Dostert was presenting papers and new research up until his death.