Title: Diego Asencio (SFS’52) is held hostage by revolutionaries while Ambassador to Colombia.

Diego Cortes Asencio graduated from the School of Foreign Service in 1952, after which he completed his military service just in time to catch the end of the Korean War. In 1957, Asencio joined the U.S. State Department Foreign Service as one of its first Hispanic officers; he had been born in Spain to a Spanish father with naturalized American citizenship. In an interview, Asencio describes how his father had encouraged him to embrace both his Spanish and American side, which he believes led him to pursue a career in the U.S. Foreign Service permitting him to engage with his own biculturality. He worked initially in the Bureau of Intelligence Research, beginning a 23 year-long relatively peaceful, successful, career in the Spanish and Portuguese speaking worlds, during which he worked up the chain to achieve positions of greater and greater responsibility.

Asencio credits his success during this time to the rigors of Georgetown’s pedagogy, where he learnt the details of world and American history as well as political science. Among his mentors from his time at Georgetown, Asencio counts the renowned Dr. Carroll Quigley whose Development of Civilizations class has been cited as a key influence of President Bill Clinton. He also names Dr. Walter Giles, who was much loved by students for his Madison Martini lecture, in which he used to describe the U.S. Constitution’s separation of powers with the analogy of a martini and the perfectly balanced three ingredients therein. His first foreign posting was in Mexico City in 1959. He later moved on to Panama, where between 1962-4 he was a Political Officer working on negotiations associated with the US-Panama Canal Treaty. Between 1964 and 1967, Asencio was back in Washington, where he continued to work on Latin American issues. His next overseas appointment was to Lisbon, Portugal, where he was rose to be Deputy Chief of Mission. In 1972, Asencio was transferred to Brazil, where he worked as the Counselor for Political Affairs. He again became the Deputy Chief of Mission, this time in Venezuela from 1975 until 1977, when he was made the United States Ambassador to Colombia.

During his tenure as Ambassador, Asencio consistently warned his bosses back in Washington about the destabilizing influence that the enormous American market for narcotics had on Colombia. He praised the Colombian government’s efforts to curb the flow of drugs northwards. However, it was not drug trafficking that would prove Asencio’s greatest challenge during his time in Bogota.

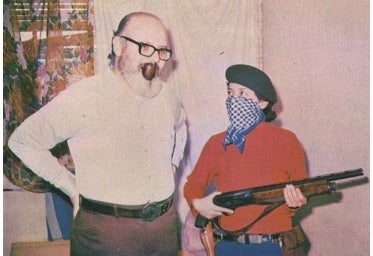

In 1980, Asencio was attending a reception at the embassy of the Dominican Republic celebrating the country’s independence. A large contingent of Bogota’s diplomatic contingent was there, including representatives from Israel and even Vatican City. As the Ambassador was about to leave, eager not to be late to his next appointment, sixteen fighters affiliated with M19, a radical socialist guerrilla group, stormed the building firing off rounds. This prompted a gunfight as security and police exchanged fire with the heavily armed M-19 members. The fighters used the diplomatic personnel as hostages to prevent the storming of the building by the Colombian security services. For the next 61 days, Asencio and other notable guests at the ruined reception were held in the confines of the embassy by the M-19 guerrillas, who were under the command of the so-called “Commander One.” His plan was to use the hostages to negotiate for the release of some of his comrades, and to get a ransom from the Colombian government of $50 million.

During a later exchange of fire, one guerrilla, who had taken a particular dislike to Asencio used him as a human shield. The Brazilian Ambassador, upon seeing this, pointed out that while in theory all ambassadors were equal, obviously the representative from the United States could be used as a valuable negotiating chip. The Brazilian continued, suggesting that if the hostage-takers wished to use a diplomat as a shield, “Why don’t you use one of the Central Americans?” Asencio reports that in these dangerous moments, he was able to take solace in the Catholicism that he learnt at Georgetown, experiencing what he calls his “most sincere act of contrition.”

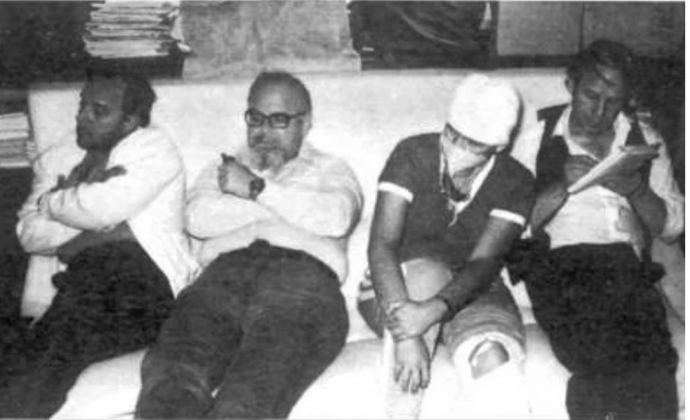

At the encouragement of Commander One, the hostages organized themselves into a negotiating group, for which Asencio was selected, along with the ambassadors from Brazil and Mexico. The group fostered good relations with their captors to ensure that they were well treated, and even went so far as to try and affect the direction of negotiations. In this endeavor, the committee of ambassadors succeeded in convincing the hostage-takers to release the women and the wounded so that they could maintain the international image of being ideological warriors, whose battle was with the Colombian government. After what seemed like endless rounds of negotiations, in which Asencio played a key role in moderating the two sides, over the course of several weeks, the hostages were informed that the Communist Cuban government, under Fidel Castro, had offered sanctuary to the guerrillas and protection for the hostages. The end of the ordeal had finally arrived.

After his safe return to the United States, Asencio received the State Department’s Award for Valor, as well as the Constantine E. Maguire Gold Medal from Georgetown University. He soon became Assistant Secretary of State for Consular Affairs, before attaining his final posting in 1983 as U.S. Ambassador to Brazil. He retired from the State Department in 1986. He now spends his retirement in Florida co-writing books with his wife, Nancy, about their experiences as a diplomatic couple. Their jointly written titles include Our Man is Inside and Diplomats and Terrorists Or: How I Survived a 61-Day Cocktail Party.