The change, which was decided upon through discussions with students, faculty, and alumni, was initiated with the school’s hundredth anniversary in mind: “Upon the SFS Centennial, we must assure that our students are prepared to make a positive impact on a new century,” says SFS Dean Joel Hellman. “That means solving global problems involving science and technology that are central to today’s world. The SFS curriculum will change to keep our school—and our graduates—leaders in global innovation.”

The new SFS science classes, however, will not be the standard “Introduction to X Science”, but will be specifically tailored to ensure relevance to global affairs and pressing world issues. In order to establish science’s place in the SFS core curriculum, two new faculty members have been brought on board: Cynthia Wei, who is spearheading the new initiative, and Clare Fieseler (SFS’06).

Professors Fieseler and Wei have similar but divergent scientific backgrounds. Both are ecologists, though the former focuses on marine and coastal ecology, while the latter did her Ph.D. in animal behavior. However, they share a vim for the importance of science to international affairs and imparting that knowledge to SFS undergraduates: “For students interested in working across international boundaries on problems, at the end of the day who are interested in making the world a better place, I think science has a fundamental role in those endeavors,” states Wei. She has a clear view of science fitting into the Jesuit emphasis on service and being “People for Others.” Professor Fieseler likes to take her cadre of students, in “The Science of Extinction and De-Extinction,” out of the classroom. On a recent trip to the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, students went behind the scenes to work with researchers and the fossils. Fieseler explained how they discussed getting these public sphere resources “more available through digitization to understand how those collections can help more people research and understand, not only the fossil record, but why we’re here and what we’re going through with extinctions.” Science, both Fieseler and Wei note, is intrinsically global. The problems it confronts and attempts to solve have no respect for national borders. As a result, they both see the addition of this component to the SFS core curriculum as a natural next step. The rollout of the science program is part of the celebration of the SFS centennial, as Fieseler says, while “reflecting on the past it is natural and appropriate to be reflecting on the future.”

Fieseler and Wei agree that the next generation of global leaders must be science literate. “Having the science requirement at the SFS will bring a more realistic angle and perspective on the emerging global challenges, like climate change, like food production. It brings the SFS up-to-date after being a hundred year organization,” says Fieseler. Wei asserted that not only does the SFS need science, but science might benefit from a fresh perspective. She admits that “there are challenges to teaching students who aren’t as interested in science,” of which the SFS undoubtedly has a number, but because of their other interests, these students approach her class, entitled “Examining Crises Through the Lens of Science,” with a “problem solving lens. They’re looking maybe more for the societal relevance.” Wendy Xiaowen Xia, a first-year in “The Science of Extinction and De-Extinction,” illustrated this emphasis on practical applications that SFS students use when thinking about science: “In an age where the line between truth and fiction is so blurred, informed decisions and policy-making have become increasingly important. I think that it is thus crucial for someone studying international affairs to also be informed of objective matters at hand.”

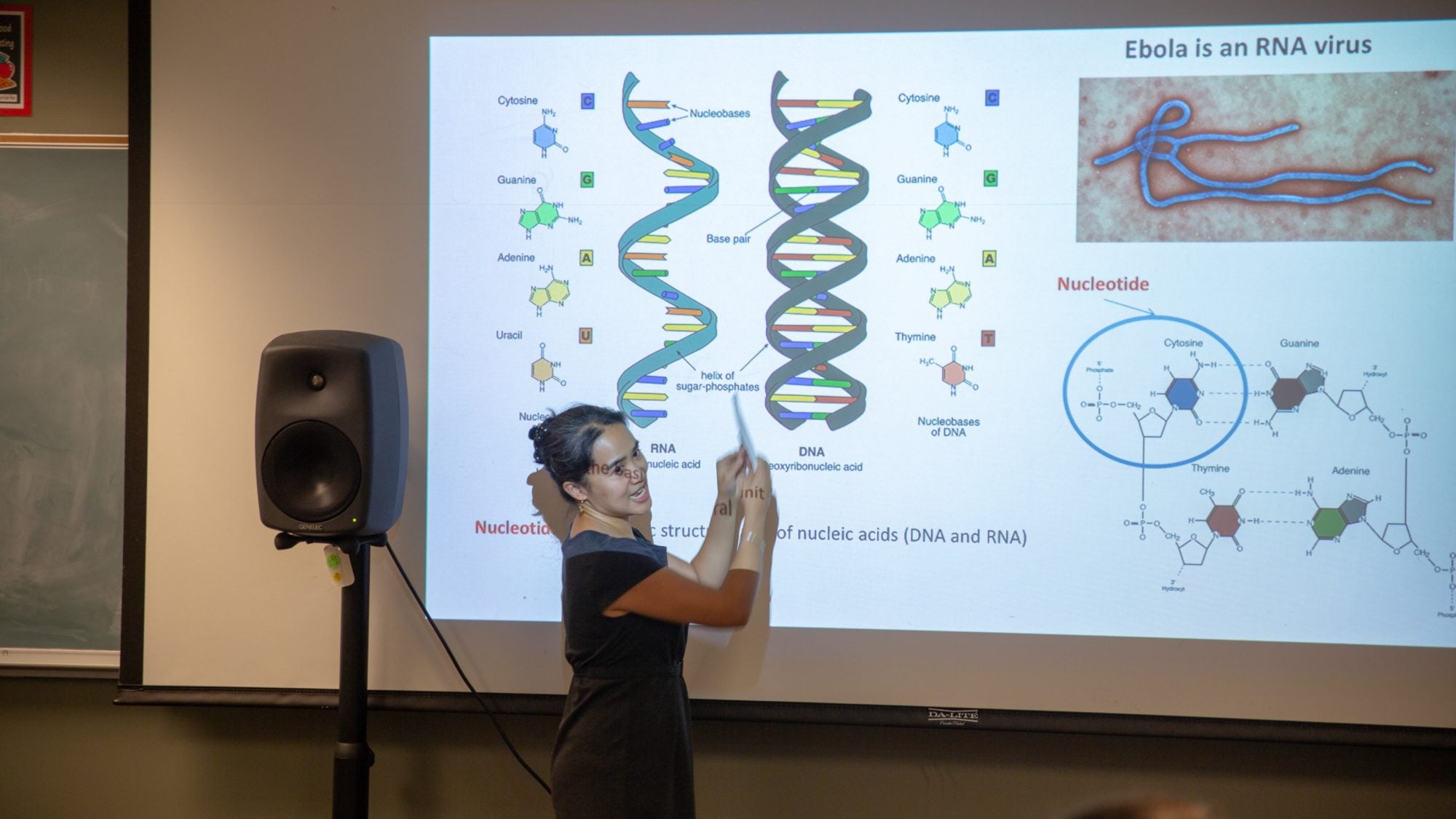

The key to these new classes, according to Fieseler who relayed the advice she received before her interview, is to make science fun while simultaneously relevant. Students have made trips to the Lauinger Library Makers Hub, a specialized space on campus for creation and invention, to 3D print ancient dolphin skulls, given Ebola genome sequences and told to decipher the puzzle, and taken trips to labs and museums. Student testimonials show that, so far, the program is a great success. SFS first-year Sarah Bryant, also in Professor Fieseler’s class, admitted she’d never intended to seriously pursue science beyond the high-school level and that she didn’t initially understand how the discipline would fit into her international relations degree. Now, however, her perspective has changed: “This class is showing me how science ties in very practically to global events, and assignments like writing policy memos have helped me see how integral science is to many policy questions.” Fieseler and Wei are working towards the expansion of the program; and both professors have exciting plans for different and exciting classes in the future that are sure to make students adjust how they think about science.

“This class is definitely one of the most interdisciplinary and thought-provoking courses I am taking this semester,” say Chae Lin Park, SFS first-year in Professor Wei’s class. “The in-depth investigations motivate us to constantly evaluate a large amount of knowledge and come up with our own critical conclusions.”

As stated, SFS students are no longer “safe from science,” but instead will be encouraged to actively engage with the discipline while thinking about global scenarios. In these classes, students will have to grapple with technical questions, policy problems and ethical dilemmas that directly affect the world of international affairs. In this way, at the 100-year mark, the SFS is modernizing to produce the next generation of global leaders.

Special thanks to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Dr. Nicholas Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals, who engaged in a three class collaboration on paleobiology with Georgetown students.