Culture Transforms Post-Conflict Cambodia

The Khmer Rouge’s violence resulted in the death of over a third of Cambodia’s population. Around 70 percent of the country’s population today is under 30 years of age, and almost everyone in the nation lost relatives or friends during the genocide, according to Goldman.

Although the UN-backed Tribunal for Cambodia has convicted three members of the Khmer Rouge, people with former connections to the Khmer Rouge still remain part of Cambodia’s government and social fabric. Though many Cambodian people have reconciled with one another and moved forward, the ghost of the past remains infused in the country’s identity 40 years after the end of the genocide.

As the country continues its revival, which has included more than two decades of strong economic growth, art has been the mechanism that has truly healed the wounds of a splintered society, says Schneider.

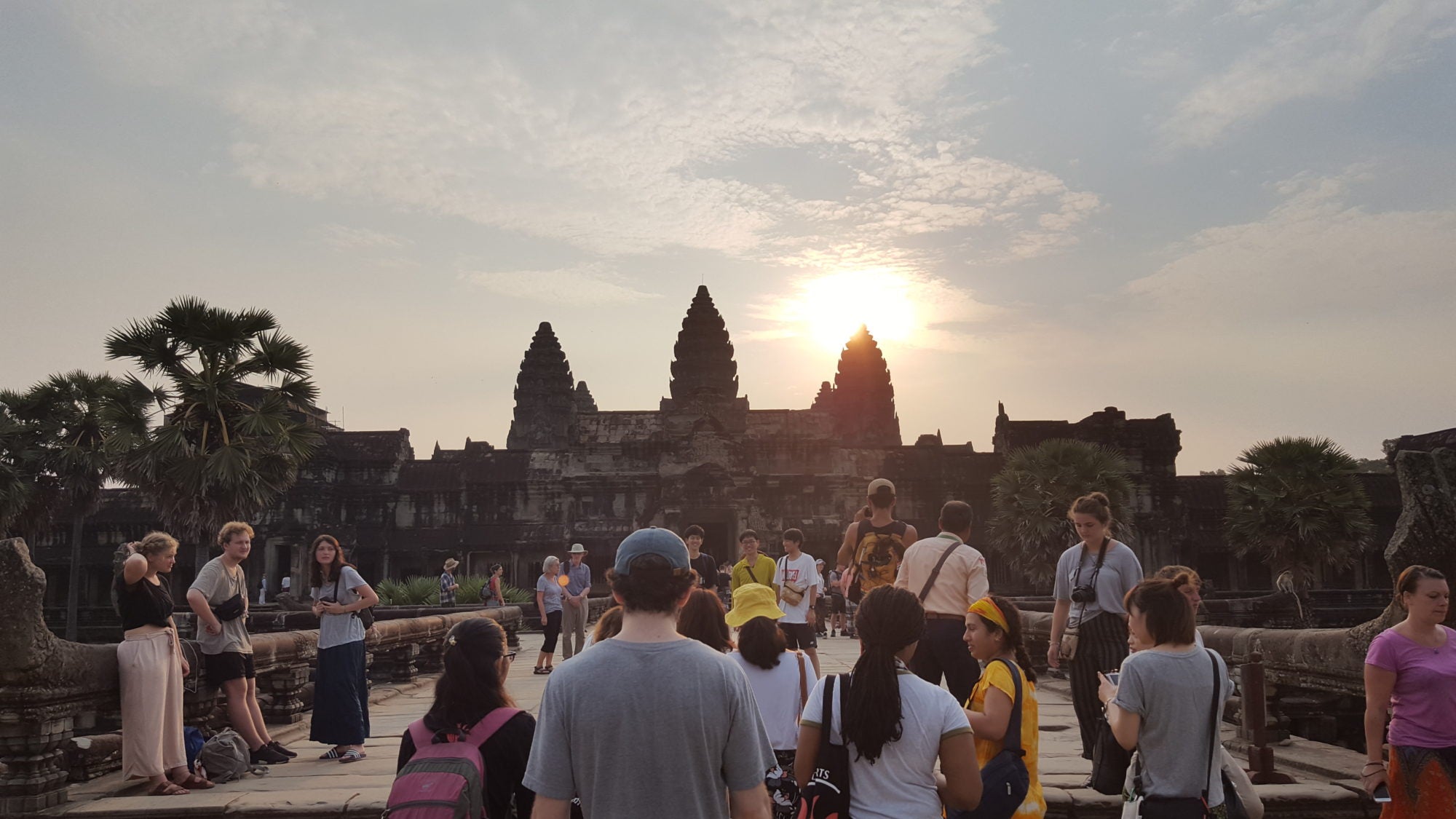

“A key factor in fueling the country’s economic growth has been the tourism industry around Angkor Wat, so their historic culture played a very important role in the economic revival,” says Schneider. “But in terms of rebuilding the sense of identity, a sense of resilience, a sense of hope, a sense of possibility for the future, the revival of the arts has been absolutely essential.”

Artists were among those first targeted by the Khmer Rouge’s violence. 90% of them did not survive the regime, and traditional arts in Cambodia were in danger of becoming extinct. Cambodian civil society has taken the lead since the end of the genocide in protecting, promoting, and advancing their culture. Cambodian Living Arts is one of the organizations that has spearheaded this work.

In light of this, Cambodia represented an ideal case study for Georgetown students to witness the value placed upon cultural leaders in rebuilding identity and shaping a vision for the future.

“Even beyond the degree to which I anticipated, it’s really the perfect living field site, the perfect case-study,” says Goldman.

“I think the hope for the trip was to get as many perspective and angles, when you travel to a place like that, you’re not just speaking about something, you’re living it, you’re smelling it, you’re feeling it, you’re in the texture of the places and the people and the language.”

Using the Past to Shape the Future

The group followed an intensive schedule throughout the trip, visiting sites of remembrance and watching a wide range of performances — from drumming groups, to dance troupes, to a circus — and meeting with the artists behind them.

The students not only gained unique insight into the country’s history and politics through the themes of these performances, but by meeting the artists meetings, also learned about the value historically placed on the arts, and the way the arts are growing and being used today—not only to revive Cambodian culture but also to heal the country after national trauma.

Goldman highlighted a performance by the Phare Circus, a circus company that trains young artists who seek a sense of identity and home.

“We saw a piece, that, number one, was artistically so on fire, they were amazing because it reflected without much spoken language all of the political, social kind of meaning that we were experiencing were embedded in the performance,” says Goldman. “You could see that the students, we didn’t need to have a deep seminar, intellectual conversation, they just were receiving that.”

Artists in Cambodia play the crucial role of presenting commonly felt sentiments of citizens and advocating for social change.

Some, including a pair of all-female dance and drumming troupes whom the students met with during the trip, are even using traditional forms of art to challenge pre-established social norms, such as those governing gender roles.

“It just so happened, that on International Women’s Day we met with two all-female groups, one a contemporary dance troupe that has actually been banned from performing in pagodas by the arts authority in Cambodia and the other a women’s drumming group, which breaks all the conventions of women aren’t supposed to drum, only men are,” says Schneider. “And these young women spoke so eloquently about how they were breaking out of the traditional confines of female identity in Cambodia through their art.”

Many of the students are very similar in age to the artists they met, so the trip represented a valuable opportunity for the students to witness the way their peers in Cambodia are assuming the role of cultural leaders and generating impact within their communities.

“I was awestruck watching artists engage all forms—dancing, drumming, sculpting, and even the circus!—as a way to talk about Cambodia’s very recent traumatic past under the Khmer Rouge, and as a way to empower marginalized people in Cambodia’s present,” says Sarika Ramaswamy (SFS ’18).

The students even had the opportunity to take workshops, playing instruments, acting, and dancing alongside professional artists.

“We were seeing work by the leading artists in Cambodia, but we weren’t just seeing it as audience members,” says Goldman. “We were spending time with them and hearing their stories and hearing what they struggled with. And students got to make work with them, to have workshops and share their practices in a really intensive way.”

Building Connections

The trip left a deep mark on the students. Despite only lasting for a week, their stay in Cambodia was a was a transformative experience that left students wondering about the role that art played in their own cultures, according to Schneider.

“I really hope that they come away from the course with a deep and really nuanced understanding of the role that arts and culture can play in different societies, particularly in a post-conflict situation,” Schneider says.

Both directors highlighted that, as the students themselves came from a wide range of national, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds, they drew very personal connections between their experience and their heritage. The trip left them eager to continue exploring these linkages.

“Some are creating performances and reflective papers since they’ve come back that are deeply personal in nature, and also critically rigorous because they are developing new lenses to see into their own cultures and their own histories and their own passions,” explains Goldman.

Some are even thinking about changing their academic focus, returning to Cambodia, and finding ways to continue working with Cambodian Living Arts.

“Learning about the authority in Cambodia and its similarities to other international crisis opened my mind to how important it is to encourage culture and art as a means to connect and strengthen a body of people that has been more or less deconstructed,” says Myiah Smith (SFS ‘20).

Goldman considers the bonds the students formed while there to be the most valuable outcome of the trip. He hopes continue to work alongside some of these artists, maybe even bringing them to Washington, D.C.

“I always say about theatre and the arts, it’s not about product, it’s about process and relationships and what you can do next,” says Goldman.

“When you just go on a great trip and you’re like, ‘we’ll have those memories forever’ and you look back at your pictures. For us, these are really relationships.”

Both directors see the trip as a watershed moment for the students and the program alike.

“It really feels more like a beginning than an ending, and I think that’s true for the students too,” says Schneider.