From concert halls to local singalongs, George Frideric Handel’s Messiah stands as a testament to the enduring power of participatory art, captivating audiences for centuries with its triumphant joy. Yet, behind this musical masterpiece of hope lies a story of upheaval and uncertainty, rooted in the turmoil of early Enlightenment Britain—a period marked by dazzling creativity but shadowed by empire, war and existential debates over truth and power.

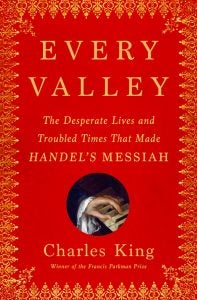

In his new book, Every Valley, SFS Professor Charles King brings this world to life, illuminating the personal and political dramas that converged to create a cultural phenomenon. King takes us behind the scenes of his storytelling, revealing how unlikely characters and their struggles made Messiah an enduring work of resilience and hope.

Q. In your book, you describe Messiah as a pathway through some of life’s most perplexing questions. How did the personal struggles of those who inspired its creation shape the philosophical undercurrents of the work?

A. Messiah is one of world civilization’s great monuments to the possibility of hope. That’s an especially strange fact about a work that came out of the dark shadows of the Enlightenment. Anyone alive at that time, in early eighteenth-century Britain, would have experienced a world awash in war, disease, children abandoned to their fate, brutalized women and, of course, an economy entangled with empire and human enslavement. So I wanted to explore the fact that a work of music about hope came from a moment when people could feel the need for it. That’s what most amazed the work’s earliest audiences and continues to move people today: that the words and music feel like they were somehow written for our own moment.

Q. While many consider Messiah a singular artistic achievement by Handel, you emphasize the collaborative nature of its creation. Could you share more about how the contributions of marginalized figures—like Ayuba Diallo, an African Muslim—influenced the final piece?

A. Messiah came out of one of the great unsung collaborations in cultural history: Handel himself as the creator of the music and an obscure figure named Charles Jennens, who arranged the libretto, or the words and scenic structure. Handel and Jennens were opposites in many ways. Among other things, the deepest political divide of the time ran through their friendship. Handel was a servant of the British king, as court composer, while Jennens was part of a political faction that believed an exiled royal line, the Stuarts, were Britain’s legitimate kings. I also wanted to write the stories of the many other people whose lives were directly and indirectly tied to Messiah’s creation.

Ayuba Diallo, for example, was an enslaved African man who, after being freed from captivity in Maryland, briefly became the toast of London society at the time Jennens was sitting down to compile the text of Messiah. Diallo and Jennens were even members of the same learned gentleman’s academy, even though they likely never met. Diallo’s life was emblematic of the way in which the proceeds from slavery were woven into British society in this period—as well as its own kind of redemption story. He ended up being one of the very rare individuals whose life we can trace from captivity to freedom and all the way back home to West Africa.

Q. You situate the creation of Messiah in a time of anxiety and intrigue, scandal and satire. What parallels do you see between the eighteenth century and our current era, and how can Handel’s work resonate today?

A. I wanted to make those parallels implicit in the book rather than hammering the comparisons with the present day. But you can’t look at eighteenth-century Britain and not find some resonance. This was the era of the birth of modern political parties. People expressed their disagreements in cartoons, plays and pamphlets in much the way that social media works now. Anyone with an opinion seemed to want a way of expressing it publicly in print. Daniel Defoe, for example, marveled at how news seemed to travel instantly around London in ways that would have amazed an earlier generation.

Q. Although originally composed for the Easter holiday, Messiah has become a beloved, participatory tradition of the Christmas season. How did it evolve from a specific historical moment into the timeless experience it is today?

A. The slide toward December had already taken place by the early nineteenth century. It was likely part of the more general trend of Christmas overtaking Easter as the major Christian holiday, along with the expansion of Christmas as a secular celebration. All of that has made Messiah as much a part of the holiday season as warm spices and spruce trees. But I wanted to try to make Messiah seem weird and new, and very much tied to the politics and philosophy of its day—which is how its earliest listeners would have experienced it.

Q. The book intertwines Enlightenment ideals with the music’s message of hope and redemption. How does Messiah reflect or challenge Enlightenment thinking, particularly in relation to justice and truth?

A. Many people might see the Enlightenment as about the triumph of reason and the birth of modern science. But there were many Enlightenments, and one of the deeper themes of the time was the problem of how to manage catastrophe. Jennens’s libretto is a Christian’s attempt to use the raw material of his religious tradition to create a kind of philosophical guidebook to hope, wonder and awe—which are also Enlightenment themes, as it turns out. Jennens took Bible verses from the Hebrew prophets, the Psalms and the New Testament, but then rearranged them in an order that made sense to him. That’s why every performance since 1742 has begun with the sung words “Comfort ye.” Even beyond the theology, the message of Messiah is about how to rethink your day or even your life, by putting an assurance up front—which is something that I think audiences are still moved by today. So, Every Valley is a work of history that tries to recreate a moment when faith, politics and philosophy were braided together in a work of art that we still find mesmerizingly beautiful.