“I hardly run into a dull conversation here,” says Tristin Sam (SFS’23) of his experience at the Walsh School of Foreign Service (SFS). “The concentration of knowledge and unique people have always provided me with great experiences and insight.”

In particular, Sam values the conversations he has with fellow activists on Georgetown University’s Native American Student Council (NASC). A student-run organization that advocates for Indigenous students, Sam has been involved with NASC since he arrived at Georgetown.

Over the past two years, he has pushed for increased outreach to Indigenous prospective students, university recognition of Indigenous People’s Day and official acknowledgement of the Indigenous nations who have traditionally called Washington, DC, home.

Now the club’s president, Sam believes that deeper engagement with Native issues would strengthen SFS students’ understanding of international relations and the history of U.S. foreign policy, as well as create a more inclusive environment for Indigenous students.

“The United States and other nations that perpetually occupy Indigenous homelands have a responsibility to increase the welfare and representation of their original stewards,” he says. “One of the first steps on this process is education and the quelling of ignorance and avoidance of these issues. The SFS has a beautiful opportunity to aid in this beginning step.”

Recognition and Representation

Like many SFS students, Sam was first introduced to the world of international affairs through a Model United Nations (UN) conference he attended in high school. “I enjoyed the topics taught that day a lot,” he recalls. “I figured since SFS was the best international relations school out there, I wanted to be a part of it and get the best education out there on the subject.”

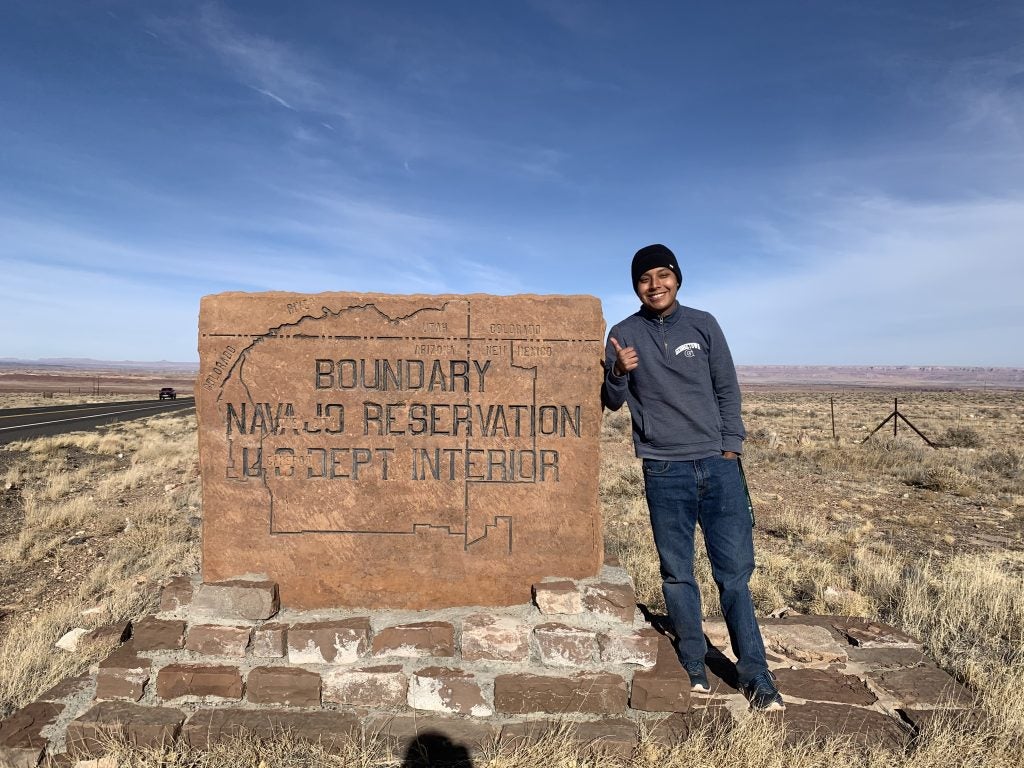

Through Model UN, students learn about foreign policy and diplomacy by representing the UN delegation of a sovereign nation in an extracurricular international relations simulation. But despite an 1868 treaty with the U.S. government that established its sovereignty, there is no delegation for Navajo Nation, where Sam grew up. Nor is there formal representation for Yavapai-Apache Nation, of which he is a registered member.

This exclusion of Indigenous people from international policymaking extends to a similar lack of recognition and representation in powerful institutions around the world. Despite the fact that between 350 and 500 million people around the world identify as Indigenous, Sam is one of only a few such American Indigenous students currently enrolled at SFS.

Sam says that ensuring Indigenous SFS students feel involved in a larger community is one of the primary goals of NASC. Since his first year at Georgetown, he has been involved in the club’s social media outreach and awareness campaigns, offering resources to Native students and encouraging non-Native students to educate themselves on Indigenous issues.

“I oversaw our social media platforms and our newsletter,” he says. As NASC president, Sam is now responsible for coordinating this messaging, as well as calling on administrators to prioritize the needs of Indigenous community members. “I have managed the administrative aspects of the organization, as well as organize events, advocate on issues important to NASC to the administration and other organizations and ensure NASC provides a sense of community to Indigenous Peoples on campus.”

Specifically, Sam and other NASC members are focused on convincing the university to enact a proposal to increase the representation and improve the experience of Indigenous students on campus. The proposal, which the club submitted to the Office of the President in 2019, recommends measures such as the inclusion of the experiences of Native American and Pacific Islander people in the core curriculum, the creation of a Native Studies major or minor and a more active effort to recruit Indigenous students and faculty, NASC members hope the adoption of the petition would improve the resources and support available to Indigenous people at Georgetown.

“The organization put out a petition imploring the university to increase representation and support for Native American, Native Alaskan and Indigenous Pacific Islander students on campus,” Sam explains. “Unfortunately, all the action items listed in the petition have still yet to be addressed.”

As the organization pressures administrators, Sam and his colleagues have continued to raise awareness of Indigenous issues in other areas of campus. “NASC during this time have met with multiple organizations and devised strategies to increase Indigenous awareness among the student body and more inclusive spaces for Indigenous students and visitors,” he says.

Broken Treaties: Toward A More Informed Vision of International Relations

Sam believes that a deeper and more rigorous engagement with Indigenous issues would not only create a more supportive environment for Native students like himself, but it would also empower all SFS students to take a more honest look at U.S. foreign policy.

“The United States violates international law everyday by not upholding its treaty obligations with countless numbers of tribes,” he says. “It is mostly forgotten by even academics that tribal nations were among the first foreign entities the United States conducted diplomatic relations with after its independence. Every tribal treaty went through the same process of approval as any other international treaty the United States has signed.”

By ignoring this foundational aspect of U.S. diplomacy, Sam says, international affairs students and practitioners undermine their own positions on human rights violations in other countries. He highlights how Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders pointed to American abuses against Native people as a way to deflect from condemnations of the Holocaust. Sam adds that, today, similar rhetoric emanates from Chinese Communist Party leaders about systematic violence against the country’s Uyghur population.

According to Sam, this whataboutism will continue to haunt the U.S.’s efforts to promote human rights abroad until the country takes responsibility for the genocide of Native Americans.

“In the realm of international affairs, it is this current state of Indigenous Peoples we find ourselves in that foreign actors latch upon to throw accusations to justify their own injustices it commits against its own people, the same injustice the United States committed against us,” he says. “The only way to counter these accusations is for the United States to strengthen its commitments to amend these wrongs.”

Sam insists that making amends is a multigenerational process, but he has some recommendations on how to start. First, including — and even requiring — classes on Indigenous issues in SFS curriculum would capitalize on growing student interest on the subject and compel non-Native students to learn more about a history that may have been erased from their previous studies. “The interest of the student population in learning about said topics is high. There are currently, however, very few classes and resources to direct their interests to,” he says.

Just as important as the content of these classes are their instructors. Sam adds that efforts to expand course offerings on Native themes must be accompanied by a more active effort to recruit Native faculty and students with lived experiences in the areas about which they would be teaching and learning.

“Indigenous voices are the best to educate on these issues and Indigeneity itself,” he says.

“We Have Survived Loudly”

Helming Native advocacy efforts as president of NASC is full of challenges, and Sam credits a close-knit network of fellow activists with helping him juggle these responsibilities. When asked about the community members who have had the biggest impact on him at SFS, Sam had a special message for the alumni, students and faculty who have supported him over the years.

“I would like to shout out to the previous NASC members Yasmin, Ian and Cheyenne, Alanna and the current members of NASC, as well as Professor [Shelbi Nahwilet] Meissner and Professor [Sylvia] Önder. All of you have helped on my own personal journey, and I hope to provide the same support and guidance to others the same as you all have done for me,” he says.

Sam’s efforts and those of his small team have inspired more interest in reckoning with the exclusion of Native people from SFS classrooms and community.

NASC’s colorful and informative social media posts — urging cultural sensitivity around Halloween and promoting course offerings that explore Indigeneity — are circulated more widely each semester. The club also co-hosts events with other campus organizations to connect their advocacy with other issues that students are passionate about.

As Sam sees it, NASC’s growing campus presence and specific efforts to create community for Native students attest to the bright future of Indigeneity at SFS and Georgetown.

“Indigenous Peoples have survived state-directed genocide and culturicide. Although we are still trying to piece together our severely damaged world this nation’s policy has inflicted, we have survived loudly. I am confident that we can find a balance between our two worlds. I am confident that the achievement of this goal will strengthen American messaging and position to stand for human rights around the world,” he says.

While Sam is inspired by the resilience and capabilities of Indigenous communities on campus and beyond, he says that powerful academic and political institutions bear much of the responsibility for righting past wrongs. Sincere reconciliation, he says, will mean putting Indigenous voices first.

“This process can only be achieved through Indigenous input and leadership on the rebalancing of our own world with that of the occupying one of the United States. This process will not be a quick one. It will be a multi-generational one,” he says.

“The question I have is if America will aid us in this goal.”