This story was produced in collaboration with the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy (ISD) at the Walsh School of Foreign Service. To find out more about ISD, visit their website.

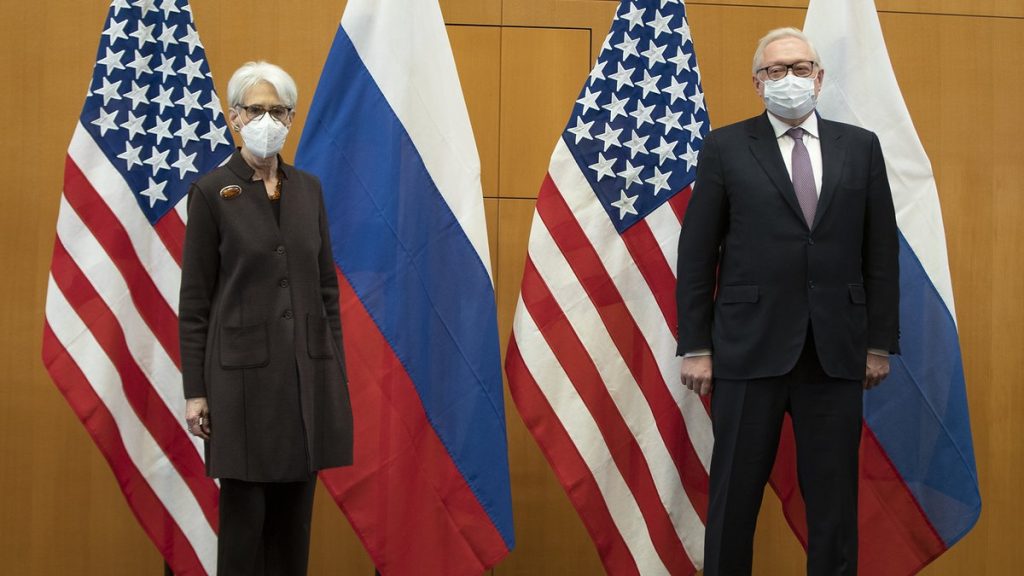

U.S., European and Russian diplomats are meeting this week in an effort to de-escalate tensions on the border between Russia and Ukraine. Bilateral talks between U.S. and Russian delegations took place in Geneva on Monday and Tuesday, followed by a NATO-Russia Council meeting in Brussels on Wednesday. On Thursday meeting, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) met in Vienna, with participation of Ukrainian officials.

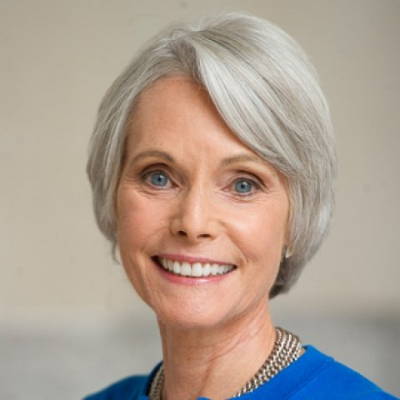

The negotiations follow months of tensions since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered around 100,000 troops to the border with Ukraine in November. “The talks are stalemated, but there is general agreement that they will continue,” Dr. Angela Stent, director emerita of the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies (CERES), who has provided extensive media commentary on the crisis in recent weeks, notes. “The U.S. side wanted to make plans for the next round of discussions but the Russian side was clearly not empowered to do so.”

Any progress in the weeks ahead will be slow. Unrest in Kazakhstan, another Russian neighbor and former Soviet republic, has regionalized the crisis and changed the calculus for Moscow in particular.

Conflict has already plagued Ukraine for the last eight years, since the previous Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014. The Ukrainian government has been engaged in long-running efforts to secure additional support from the United States and its European allies in the face of this latest Russian aggression. This week’s talks mark the highpoint of this effort, with some of the most intensive diplomatic engagement we have seen from the Biden administration so far.

To assess these efforts to avoid a major war on European soil, SFS faculty members and affiliates of Georgetown’s Institute for the Study of Diplomacy (ISD), provide insights on the status of the negotiations, the regional and international dynamics of the broader crisis and the possibility of de-escalating tensions.

Diplomacy in Action

“These talks are critical to the U.S.-Russia relationship and to European relations with Russia. For Europe, the outcome literally, as a senior Russian official put it, could mean ‘war or peace,’” says Professor Jill Dougherty, an adjunct faculty member at CERES and journalist who previously served as CNN’s Moscow bureau chief.

The talks may not be enough to quell the current crisis, she cautions, “It still is unclear whether Russia is willing to negotiate diplomatically to get what it wants, or actually wants negotiations to break down and use that as justification for military action.”

“Diplomacy needs to be backed up by action,” says Ambassador (ret.) John Heffern, distinguished resident fellow at ISD and former acting assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs. He believes that the Biden administration has the right approach, “to push Russia in three areas — deeper economic sanctions, more defensive military assistance to Ukraine and more active U.S. and Allied military presence in the east.”

“Historical context of Russian aggression on the territory of former Soviet Republics is key to understanding how to deal with the current crisis,” Heffern notes. The historical roots of the Ukraine crisis run deep, and their complexity means that this week’s talks are unlikely to resolve tensions on their own.

Ambassador (ret.) Kathleen Doherty, ISD contributing author and former senior career U.S. diplomat, agrees. “Longer-term,” she says, “President Putin wants to re-write history of the past two decades and, by pressure or by force, re-create a Russian sphere of influence and control over its neighbors.”

“A Threat to Security in the World”

It is increasingly clear, however, that diplomacy alone will only carry the United States and Russia so far. Dr. Jeffery Anderson, professor at Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies and an ISD board member, applauds the Biden administration’s diplomatic efforts, but acknowledges that there are few remaining areas for potential agreement between the two great powers.

“The U.S. has already ruled out any concessions on NATO membership or the structure and configuration of the alliance,” Anderson says. “That leaves a smaller range of issues of lesser importance to the Russians on which to find agreement. This does not auger well for the outcome.”

While public attention might be turned toward the pandemic and economic recovery, Dougherty agrees that this is a potentially perilous moment that could impact ordinary citizens.

“How these talks develop, whether they will be broken off and Russians tanks rumble toward Ukraine, or whether they continue and try to find a way to defuse this dangerous stand-off, is important for Americans,” she stresses. “What Vladimir Putin is saying is that his country has the right to a ‘sphere of influence’ around its borders on which NATO, the political and military alliance of 30 nations, dare not impinge.”

“That is a threat to peace in Europe and, ultimately, to security in the world,” she adds.

Western allies should be prepared to take action soon, Heffern says, “not when Russia actually takes military action again.” Inaction thus far has emboldened Russia’s aggressive stance and undermined the West’s ability to exert influence over Moscow. “Putin is betting that the United States and Europe will not follow on these threats, based on the moderate response by the West to Russian incursions in and seizure of Crimea,” argues Doherty.

Strains in Transatlantic Relations

To prove him wrong, the Biden administration has mounted a full-throated diplomatic effort to coordinate with its European allies. According to the White House, President Biden, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and other senior U.S. diplomats held nearly 100 meetings and calls with European allies and partners in the run-up to this week’s meetings with Russia. Effective coordination and communication with European allies was critical to the success of this week’s talks and will be essential in the event of further Russian aggression. However, strained U.S.-E.U. relationships and fragmented European politics pose significant challenges to such collaboration.

Already, European leaders have raised concerns about these negotiations taking place without sufficient European representation. “Given the events of the fall [including the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the AUKUS security pact], not to mention the track record of the previous four years, there is understandable concern in European diplomatic circles about the U.S. negotiating over the heads of Europe about the fate of Ukraine,” says Anderson.

While there may be good strategic reasons for the United States to structure the meetings this way, continuous communication with European allies throughout is nevertheless crucial, Doherty argues. “Several European officials have expressed umbrage at not being at the table with the U.S. and Russia since the matter at hand involves European security architecture,” Doherty said. “U.S. officials also need to work closely with the European Union institutions and its member states.”

Heffern agrees, but also argues that this is a moment requiring U.S. leadership. “The sequence of meetings this week has been right — first U.S.-Russia, then NATO-Russia, then OSCE, which includes Ukraine,” Heffern says. “I believe the Biden team understands that the U.S. needs to lead and we cannot adopt lowest common denominator decisions, but we also need to decide and act in close coordination with relevant allies and partners.”

A Crucial Test for NATO

Focusing on regional allies and reasserting NATO’s power in Europe is critical if conflict is to be avoided, stresses Dr. Roger Kangas, adjunct professor at CERES and a former NATO adviser. “A number of Soviet successor states strongly object to a Russian security presence in their declared territories — such as Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia — creating instability near NATO’s eastern borders,” he warns.

Kangas believes that there are some positives to emerge from the talks. “First, the fact that the NATO-Russia Council talks took place at all — and went overtime — is a sign that non-military options remain viable to lessen tensions in the region.”

“Second, after years of paying less attention to the security threats emanating from Russia, NATO and the West seems to be re-engaging on this issue. It appears that NATO is returning to some basic, long-held priorities of European security — and that of member states.”

“There are limited options for NATO in deterring a potential Russian invasion of Ukraine. Fortunately, NATO is acting within these limits,” explains Kangas, pointing to the Alliance’s continued presence in the Baltics and Poland — NATO member states that neighbor Ukraine — and the transfer of training and equipment to Kyiv.

“NATO leadership is speaking with a relatively unified voice, which is difficult for a 30-member entity,” says Kangas. This includes the potential for Ukrainian membership in the Alliance, something that many U.S. officials support but the Russian government vehemently opposes. Kangas adds, “As U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman noted the other day, NATO will not allow anyone to ‘slam closed’ the open-door policy of the organization.”

Further Russian aggression would present a crucial test for transatlantic coordination. “The challenge will be to maintain NATO unity in the face of the first signs of a Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Doherty says. “Will the fractured body politic in the United States and an inward-looking Europe — a new untested German government and a French president focused on re-election — be able to reach a consensus on what NATO should do next?”

Economic and Energy Diplomacy

Russia and the United States are both hoping to leverage economic influence to achieve their regional objectives, a strategy that will have consequences for U.S. allies. Sanctions of the sort currently under consideration by the United States would have profound impacts on the European Union, Doherty points out. “European and U.S. high-tech exports to Russia might be prohibited; U.S. and European financial transactions with Russia would be restricted. Europeans are also concerned that Russia might retaliate by slashing energy exports to Europe in the dead of winter, and with energy prices already high.”

Energy has become an important diplomatic tool for both sides. On Wednesday, Sherman told reporters that any escalation of Russian aggression against Ukraine would have major implications for Nord Stream 2, a proposed expansion of the pipeline system transporting Russian gas to Central Europe.

“Russia is a major exporter of oil, gas and sometimes coal to Europe and prefers that the supplier relationship remain the same,” says Dr. Theresa Sabonis-Helf, inaugural chair of the Science, Technology and International Affairs concentration in the Master of Science in Foreign Service program. “Reducing Russian gas to Europe, or forcing that gas to flow across Ukraine, has been a U.S. priority for several years and the U.S. has an interest in increasing liquified natural gas markets in Europe.”

Over the long term, neither country is likely to achieve its objectives but Russia possesses the upper hand in the present moment. “The E.U. is trying to move to a new and different energy system entirely,” Sabonis-Helf says. “Renewable energy is on the rise, but as it begins to comprise more and more of the grid, it brings new technological challenges. In this environment, natural gas — which has been important in the European grid for a long time — becomes even more so. As E.U. states strain to include as much renewable energy as possible into their systems, Russian gas remains a very important bridge fuel.”

Europe’s future goal to completely electrify its grid may also reduce Western allies’ ability to leverage energy diplomacy to influence Russia’s actions on the world stage. “All importers want Russia to modify its behavior, and they want to buy less from Russia in the future,” Sabonis-Helf explains. “There’s no reason for Russia to commit to the former if the latter is true and, in the present moment, prices are high and Russia has a strong hand.”

Challenges Ahead

In the short term, widespread anti-government protests in Kazakhstan — where Russian troops have intervened under the auspices of the regional Collective Security Treaty Organization — complicate the regional situation. Ambassador (ret.) Kenneth Yalowitz, adjunct lecturer at CERES, says this development presents “both a risk and an opportunity” for Russia.

“If the situation should worsen, Russia could be drawn into yet another dangerous conflict on its borders,” notes Yalowitz, a former career U.S. diplomat who served as ambassador to Belarus and Georgia. “Russia wants recognition of a sphere of influence but that sphere looks increasingly shaky,” he says. If the intervention is “swift and successful … Kazakhstanis will not turn on Moscow.”

Like Kangas, Yalowitz provides a note of cautious optimism, arguing that “Kazakhstan should be a factor causing Putin to rethink massive invasion plans when so much of his neighborhood is rising against authoritarian governments.”

According to Anderson, the worse-case scenario — a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in the event of failed negotiations — could be extremely bleak. “Unless the Ukrainian military collapses completely and rapidly, the fighting will be intense, with significant casualties on both sides,” he says. “Civilians will be caught up in the fighting, which means we would be looking at a massive humanitarian crisis right on Europe’s doorstep.”

In the year ahead, “Russia’s relations with both the United States and Europe will remain tense and largely adversarial unless there is a meaningful military de-escalation on the Russian-Ukrainian border,” says Stent. Dialogue will continue in the form of arms control negotiations between the United States and Russia, as will “discussions on cyber-security and ransomware,” she adds.

“There is at least a 50-50 chance of a new Russian military incursion into Ukraine,” she cautions, leaving a window for intensive diplomacy, backed up by a credible threat of force, to resolve the crisis.