The Early Days of the School of Foreign Service

In 1919, as Father Edmund Walsh, S.J. was assembling the faculty of the freshly inaugurated School of Foreign Service, the United States seemed to be adapting to a new role on the world stage. It had recently participated and helped win the First World War on the side of the allied powers of the British Empire and France. With the dawning of this new world order, Fr. Walsh remarked that, “Having entered upon the stage of world-politics and world-commerce we assume world-wide obligations. Our viewpoint can never be quite the same again.” Despite Washington’s eventual withdrawal into isolationism with the Senate’s refusal to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, Fr. Walsh envisioned the establishment of the SFS as an opportunity to depart from the traditional Eurocentric view of foreign affairs.

One of the first professors at the SFS was Chinfu Wang-Shia, a professor of Chinese language and former Brigadier General of the Republican Chinese Army. Wang-Shia had made a name for himself during the conflicts surrounding the toppling of the last of the Chinese imperial dynasties, the Qing, and established the Republic of China. He was elevated to the rank of General following the Battle of Nanking when he and 10,000 of his men stormed the forts atop Purple Mountain that overlook the city. During the charge, Wang-Shia had his horse shot from beneath him twice and sustained an injury in his right leg from a cannonball splinter. Following his recovery and the end of the war, Wang-Shia attended Columbia University to attain a degree in Constitutional and Administrative Law, hoping to bring his new expertise back to China to shape his home country’s political system. Instead, the General joined the teaching staff of the Georgetown SFS, in its first year of teaching. He engaged actively with the student body, even speaking at one of the first events of the Delta Phi Epsilon Foreign Service Fraternity that was founded at Georgetown.

In 1924, the first Chinese student, Wai-Hing Tso, graduated from the School of Foreign Service. The yearbook of his class describes Tso as an “energetic son of China.” Prior to moving to the United States, he had studied at Queen’s College in Hong Kong, and completed a course in business in Peking (now Beijing). In Washington, Tso initially studied at George Washington University, but eventually obtained his Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service from the SFS, where he focused on the commercial side of international relations with language skills in his native Chinese, as well as French. In addition to carrying out his duties as a student, Tso acted as the Secretary of the Washington Chinese Students’ Club.

The SFS and American-Chinese Diplomacy

Many SFS graduates went on to become Foreign Service Officers who served in China or in other ways directly influenced the contours of the U.S.-China relationship.

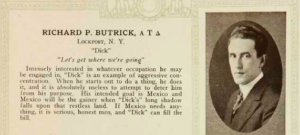

Richard P. Butrick (SFS’21), a graduate of the school’s first class, went on to a posting in the U.S. Consulate General in Hankou, now a section of the city of Wuhan. In a State Department interview in 1998, Butrick recalled first seeing the forces of the Chinese Communists, who were coming up from the South as part of the Long March that eventually brought Mao Zedong to power. On one notable occasion, the consulate staff were forced to stay overnight on a U.S. patrol ship in the town’s harbor, out of concerns for their safety, as the Communists solidified their control over the town. From Hankou, he was elevated to positions in Shanghai and Beijing, where he first encountered the aggression of the Japanese, when their navy took over the city. Following Pearl Harbor, Butrick presided over the lowering of the American flag in the Consulate, which he kept with him until he returned to China following the war and was able to re-raise it. For six months, Butrick was in Japanese custody before he was permitted to find passage to Singapore and eventually the United States.

Another SFS graduate, Raymond P. Ludden (SFS’30) was similarly imprisoned by the Japanese while serving in China. He had been in China since 1932, and after his release brokered by the Red Cross, he volunteered to return as part of an elite political team headed by Joseph Stilwell. The group travelled hundreds of miles behind Japanese lines into the interior of the country in order to make contact with and appraise the strength of the Communist resistance forces at Yan’an. For this daring journey, Ludden was awarded the Bronze Star. Following the war, Ludden remained in China and sent reports back to Washington warning of the imminent Communist takeover, and the Chinese Party’s alignment with the Soviet Union. He finally left the country in 1949 after the Communist government was toppled by the forces of Mao.

Alexis Johnson (SFS’32), a foreign service officer known as an expert in East Asian affairs, was praised by Secretary of State Dean Rusk at the time of his retirement after 42 years at the State Department as a “towering contributor” to American diplomacy. Just like his colleagues Ludden and Butrick, Johnson found himself in Japanese custody at the start of World War II, due to his position as vice consul in Manchuria at the time of Pearl Harbor. After the war, Johnson acted as one of the chief negotiators for the truce that ended the conflict between U.S. and U.N. forces against the North Koreans and Chinese. In 1953, Johnson became Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, where he represented the United States in early talks with the People’s Republic of China to discuss the repatriation of U.S. and Chinese nationals. Due to the lack of American recognition of the Chinese Communist government, these talks were the principal means of communications between the two powers, until President Nixon’s visit to the country in 1972.

In 1977, immediately after the end of his term as Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger became a professor at the School of Foreign Service. During his tenure as the nation’s top diplomat, Kissinger was the principal orchestrator of Nixon’s policy of normalization of relations with China. In 1971, he made two trips there to discuss with Chinese Premier Zhou. These first forays of direct diplomacy paved the way for Nixon’s consequential visit in 1972. During his professorship, Kissinger regaled students with stories of his historic negotiations with Chairman Mao. The following year, in light of the development of relations between the two countries, Georgetown invited 52 visiting scholars from China to study English, before they went on to other universities across the country. Dennis Wilder (MSFS’79), Managing Director of the Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues at Georgetown and Assistant Professor of the Practice in Asian Studies, cites taking a seminar with Professor Kissinger as the most impactful event of his Georgetown career. Wilder went on to spend 37 years as a CIA analyst and manager dealing with China. He also served four years in George W. Bush’s White House as a senior director for East Asia on the National Security Council and Special Assistant to the President.

The Later Years

In 1997, Wang Yi arrived at Georgetown as an associate visiting scholar for the academic year with the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy on a scholarship from the Chinese government. Since 2013, Wang Yi has served as China’s Foreign Minister. Yi studied at Beijing International Studies University and had served as a diplomat. Following his return from Washington, Yi was quickly rose within the cadres of government. He became a Minister Assistant and, in 2001, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. Since 2018, he has also served as a State Councilor, a position of enormous power within the government’s executive branch.

Xiaofei Wang (SFS-Q’16), the first Chinese student at SFS Qatar, was awarded the Qatar Foundation Scholarship, a merit based scholarship for students enrolled in institutions in Education City, where SFS Qatar is based. In an interview, Wang praised the community and the number of opportunities at the SFS in Qatar: “I finally got a chance to see what the traditional experience of college really looks like,” said Wang. “When you’re walking around, you feel like there are a lot of things to do.” As he approached graduation, he admitted that what he’d miss the people he had met most of all.

When the School of Foreign Service first opened, it embraced the expanded worldview that was the spirit of the age. In recognition of the importance of a non-Eurocentric education, the School hired Chinfu Wang-Shia to teach Chinese. Many graduates went on to celebrated careers that influenced American perspectives and policy on China. 100 years later, the SFS remains committed to a global education, one which acknowledges the importance of Asia, especially China. The Asian Studies program, founded in 1980, has an undergraduate and graduate certificate, as well as a demanding Master’s program. In addition, Georgetown University hosts the Georgetown Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues, which is a university platform for research, teaching, and high-level dialogue among American and Chinese leaders from the public sector, business, society and the academy that addresses common challenges facing the global community.